April is national poetry month

Stephen Crane and Carolyn Forché(University of Albany photo)

As is so often the case, I’ve been dallying, so I’m writing about this under the wire as it were, although most of you will only see it no sooner than Monday, May 1st.

Now, I am no poetry expert. In fact, a few years ago when I still subscribed to the New Republic a more poetically-inclined friend used to chide me for never reading the poems, TNR being one of the (very last) national mainstream periodicals that regularly includes contemporary poetry, although I’ll admit you’re probably as likely to see a copy of it at your doctor’s office as Granta or the Kenyon Review.

Anyway: non-expert or no, I thought it would be a good thing to visit the world o’ verse to see what, if anything, today’s poets are saying about the war. The first thing I found was Amiri Baraka’s “Somebody Blew Up America,” which is posted on his web site. Baraka was born LeRoi Jones in 1934 but changed his name in the 60s, and many people associate him and his work with that era. Somebody Blew Up America was composed in October 2001, and you might regard it as anti-semitic. To me, some of it is very powerful. Nevertheless, I will admit I didn’t care for his suggesting that the Jewish employees were warned not to go to work at the trade center on the 9-11. It's a canard I’ve heard elsewhere too, although I don’t think it originated with Baraka.

I had a little difficulty finding post 9-11 political verse on the net. I specifically was looking for verse from contemporary established poets as opposed to ordinary shmoes like yours truly-- not because I am one who thinks that a writer who lacks academic imprimateur is inherently not worth reading-- I don't-- but because I saw writing this post as an excuse to investigate what today’s academic poets are saying about the war and related matters.

I suspect many poets are leery of the power of the web to jerk with their intellectual property rights, and poets as a rule are not particularly well-renumerated writers, unlike say, the Million Little Pieces guy. Initially, I thought that perhaps Baraka was fairly singular among poets of his generation in having his own website, but I note that current US laureate Ted Kooser(born 1939) does too. Kooser’s site is much slicker and I couldn’t find any actual verses represented, just links encouraging you to buy his books. There is an interesting Kooser quote at wikipedia:

"Every stranger's tolerance for poetry is compromised by much more important demands on his or her time. Therefore, I try to honor my reader's patience and generosity by presenting what I have to say as clearly and succinctly as possible .... Also, I try not to insult the reader's good sense by talking down; I don't see anything to gain by alluding to intellectual experiences that the reader may not have had. I do what I can to avoid being rude or offensive; most strangers, understandably, have a very low tolerance for displays of pique or anger or hysteria. Being harangued by a poet rarely endears a reader. I am also extremely wary of over cleverness; there is a definite limit to how much intellectual showing off a stranger can tolerate."

A case could be made that this is a political statement(It's from the Midwestern Quarterly, from 1999.). But I am (otherwise) at a loss to glean any political views from Kooser.

Maybe younger poets are more likely to have an internet presence, like poetess Shanna Compton*(born 1970), and Jesse Ball(born 1978. He also doesn't post any verses at his site.)-- it’s hard to say. I did find the Nation article “Poets Against the War”(from early 2003) which includes a statement co-signed several modern American poets, including former US poet laureate Rita Dove(‘94-95) and W.S. Merwin. An excerpt:

a few of the works posted on "Poets Against the War," (www.poetsagainstthewar.org), the website set up by Sam Hamill, poet and editor, when he called for poems and statements against war in Iraq. At last count, there were 8,200 entries. Hamill's summons to poets followed Laura Bush's invitation to a symposium on American poetry at the White House, which was "postponed" when it was learned that antiwar poems were to be presented.

Statement:

It would not have been possible for me ever to trust someone who acquired office by the shameful means Mr. Bush and his abettors resorted to in the last presidential election. His nonentity was rapidly becoming more apparent than ever when the catastrophe of September 11, 2001, provided him and his handlers with a role for him, that of "wartime leader," which they, and he in turn, were quick to exploit....

Finally, a very brief sampling of US political poetry:

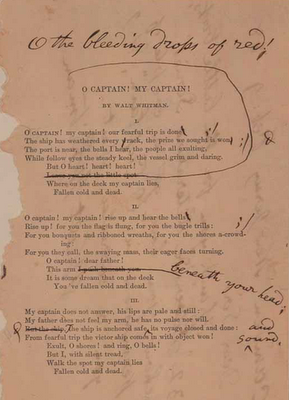

1.Only obliquely about war and politics, is Whitman’s ode to Lincoln upon his assassination:

the Library of Congress link to the proof sheet is here. (Double-click the above image for the full-sized version for easier reading.)

2.After Whitman’s dirge to Lincoln, I’m guessing that Stephen Crane’s "War is Kind" may be the most famous of US war poems. I haven’t included it here because even though it's public domain, it's on the long side, and because his oeuvre is fairly readily available online. But here’s a shorter Crane:

A man said to the universe:

"Sir I exist!"

"However," replied the universe,

"The fact has not created in me

A sense of obligation."

Ok, one more Stephen Crane. “The Successful Man”. Because I’m fond of Crane, and because this one makes me wonder what he would’ve thought of a certain well-known 21st century politico:

The successful man has thrust himself

Through the water of the years,

Reeking wet with mistakes --

Bloody mistakes;

Slimed with victories over the lesser,

A figure thankful on the shore of money.

Then, with the bones of fools

He buys silken banners

Limned with his triumphant face;

With the skins of wise men

He buys the trivial bows of all.

Flesh painted with marrow

Contributes a coverlet,

A coverlet for his contented slumber.

In guiltless ignorance, in ignorant guilt,

He delivered his secrets to the riven multitude.

"Thus I defended: Thus I wrought."

Complacent, smiling,

He stands heavily on the dead.

Erect on a pillar of skulls

He declaims his trampling of babes;

Smirking, fat, dripping,

He makes speech in guiltless ignorance,

Innocence.

His poems are like that-- unrhymed, often consciously epigramatic, and reflecting a jaundiced view of humanity. Also, they don’t have titles, and are generally referred to by their 1st lines. Crane’s verse is arguably “pre-Kafaesque”, because even though their timelines overlap somewhat, Crane was dead by 1901 and I believe that none of Kafka’s works were published until after his death in 1924, so Crane could never have known about Kafka.

3. Mark Twain’s War Prayer, which is also kind of lengthy; I posted it at HZ the week before the Iraq invasion, here. Twain wrote it in 1905 about the US war with Spain, and could not get it published in his lifetime**. Also, more readably, here.

**I find myself idly wondering if 15 or 20 years from now we'll find out about a a short play that Arthur Miller may have written in response to 9-11 and its aftermath.

4. Denise Levertov(1923-1997) was born in England but came over here in the 50s and became a US citizen. She was active in protesting the Vietnam war. From her work:

“What were they like?”

“In California During the Gulf War” (1991)

and an excerpt from “Advent 1966”:

because of this my strong sight,5. Jumping around a bit chronologically, Howard Shapiro’s(1913-2000)poetry is often associated with WWII. (He fought in the Pacific theater.)

my clear caressive sight, my poet's sight I was given

that it might stir me to song,

is blurred.

There is a cataract filming over

my inner eyes. Or else a monstrous insect

has entered my head, and looks out

from my sockets with multiple vision.

from “Hospital”:

Kings have lain here and fabulous small Jewsnot all war poetry is inevitably grim.

And actresses whose legs were always news.

6. Carolyn Forché teaches at Skidmore College in upstate New York. Some 25 years ago she wrote:

"I have been told that a poet should be of his or her time. It is my feeling that the 20th century human condition demands a poetry of witness. This is not accomplished without certain difficulties. . .If I did not wish to make poetry of what I had seen, what is it I thought poetry was?"

and, also from the early 1980s, Forche’s The Colonel:

What you have heard is true. I was in his house. His wife carried a tray of coffee and sugar. His daugher filed her nails, his son went out for the night. There were daily papers, pet dogs, a pistol on the cushion beside him. The moon swung bare on its black cord over the house. On the television was a cop show. It was in English. Broken bottles were embedded in the walls around the house to scoop the kneecaps from a man's legs or cut his hands to lace. On the windows there were gratings like those in liquor stores. We had dinner, rack of lamb, good wine, a gold bell was on the table for calling the maid. The maid brought green mangoes, salt, a type of bread. I was asked how I enjoyed the country. There was a brief commercial in Spanish. His wife took everything away. There was some talk then of how difficult it had become to govern. The parrot said hello on the terrace. The colonel told it to shut up, and pushed himself from the table. My friend said to me with his eyes: say nothing. The colonel returned with a sack used to bring groceries home.

He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like dried peach halves. There is no other way to say this. He took one of them in his hands, shook it in our faces, dropped it into a water glass. It came alive there. I am tired of fooling around, he said. As for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go fuck themselves. He swept the ears to the floor with his arm and held the last of his wine in the air.

Something for your poetry, no? he said. Some of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.

Forché went back to El Salvador 12 years later. Some of her comments are here.

Other soldiers said it was not uncommon to cut the ears off the corpses of rebels to verify enemy casualties to commanders. But officers said they frown on the practice.7. Finally, although he’s neither an American nor a versifier, Harold Pinter’s Nobel lecture(December 2005),“Art, Truth and Politics” is here.

"Sometimes in battle, my men get excited and cut the ears off the dead terrorists," the lieutenant commanding the army unit said. "It is not something we order, but sometimes the excitement of the moment overcomes them."

additional links:

Here Comes Everybody: the writers on writing blog

* from Shanna Compton’s blog, Hal Sirowitz’s

“The Hawk Who Became a Dove”(2004)

Correction: Initially I wrote that Carolyn Forché was presently teaching at George Mason U., because they still have a link up for her info. In fact, she's teaching a writer's workshop at Skidmore this summer.

<< Home